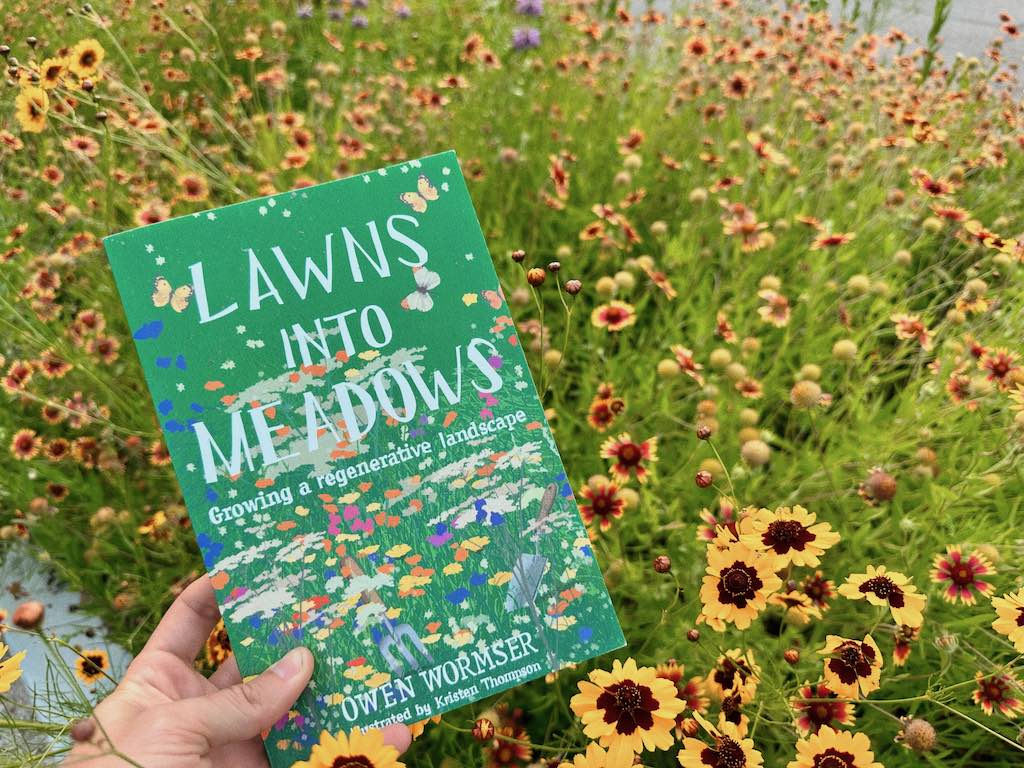

Wormser, Owen. Lawns Into Meadows: Growing a regenerative landscape. Stone Pier Press, 2020.

Five Things.

We deserve a better goto, a better default landscaping choice than the standard American lawn. One that not only consumes considerably less water, fertilizer and maintenance, but one that increases biodiversity, enriches soil health, and simultaneously removes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

We deserve a landscaping choice for our suburban land that is not only sustainable, but regenerative — a net positive.

Luckily we have one: meadows, or as we typically refer to them in the blackland prairie ecoregion of Texas: prairies.

1. Meadows allow the earth to heal itself.

Meadows are extremely proficient at storing carbon in the soil, giving back to the earth much more than they take. One might refer to a meadow as a regenerative landscape.

These regenerative landscapes increase biodiversity, enrich soil health, and remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. They first absorb carbon dioxide through the air, exhaling oxygen as a byproduct while retaining the carbon molecule to create starches and sugars they feed on for sustenance.

This sustenance of carbon-based food is shared through the plant’s root systems with organisms living in the soil, such as mycelium and microbes. When these organisms die, the carbon remains in the soil.

But meadows do more than just sequester carbon. Since meadows are comprised of a rich diversity of native plants, they offer the same earth healing properties that come with landscaping with native plants. Meadows save water, improve air quality, provide wildlife habitat, improve air quality, and reduce maintenance, thereby reducing the amount of fossil fuels and chemicals needed to maintain the land.

2. Meadows are easy to create (but require patience).

Observation is the first step. This involves studying what’s already growing in the area, especially the weeds. Plants growing in the area are good indicators of the quality of your soil, moisture levels, and how much sunlight is available.

Observations allow us to determine what plants are appropriate for our site. Once this is determined, there are two well-known rules for establishing a meadow:

- Seed into bare ground, and

- Plant native perennial seeds when it’s cool outside.

But before we sow any seed, or plant any plugs, proper site preparation typically provides better results. While you can seed directly into a freshly cut lawn, we can save on future work by tilling or solarizing the area to remove the roots and dormant seeds of plants we don’t want.

Seeding requires patience, and an element of letting go. If faster results are desired, plugs in early spring with mulch is a solution. Or a combination of seeds and plugs can be used, with the planting of plugs coming first and seeding afterwards.

Whatever the case, there are a few design guidelines to abide by:

- Use native plants.

- Start with grasses, as they are the foundation of meadows.

- Use a variety of flowers and pick colors that look good together.

- Plant for the same height.

3. Meadows are easy to maintain.

Meadows require some form of intervention to keep woody plants from taking over. Traditionally this was accomplished by the buffalo and fire, either naturally created or controlled by Native Americans.

Caring for a young meadow mostly involves weeding. But it also will likely require a bit of supplemental watering and pest prevention practice. Mowing can also be done 3-4 times a year to keep the weeds at bay before they flower, but this should be used as a last resort, except for once a year in early spring.

Meadows that were started by seed typically reach maturity within 2-4 years. Caring for them involves a single mowing in the early spring.

Why not mow in the winter after everything goes dormant? Because meadow plants supply seeds for animals and birds when food is sparse in the winter. They provide habitat for all sorts of awesome insects. And because a bunch of brown can look really cool with sunlight backlighting dormant grasses and flower stalks in the chill of February.

4. Conventional lawns are (mostly) a waste of resources.

We use an enormous amount of resources to care for over 40 million acres of turf-grass in the continental United States. 40 million acres. This is more than 63,000 square miles, or about the size of Washington state, for closely-cropped areas of turf that return very little to our environment. In fact, “a conventional lawn produced more carbon dioxide than it absorbs.” (p13)

Lawns consume a lot of time, money, and energy.

Homeowners spend an average of 150 hours a year tending to turf-grass. If you haven’t already calculated in your head, this is over three weeks of working a full-time job.

Collectively, we spend 40 billion dollars on lawns annually. 40 billion dollars for closely cropped areas of turf that equate to the size of Washington state. Is it worth spending so much money on a crop that gives back so little?

And for those who outsource their lawn maintenance, an hour of commercial lawnmower use pollutes the air as much as driving a 2017 Toyota Camry 100-300 miles, depending on the age of the mower.

Lawns consume a lot of water.

“Landscape irrigation is estimated to account for nearly one-third of all residential water use, totaling nearly nine billion gallons per day.” (p3) This is the equivalent of 13,500 Olympic-sized swimming pools worth of water. Per day.

In my area of Texas, it’s incredibly common for suburban homeowners to have a lawn comprised of either St. Augustine, Bermuda or Zoysia grass. These grasses do best on a 5-10 day water schedule, with St. Augustine being the thirstiest, and perhaps the most common.

Lawns consume a lot of fertilizer.

Americans use an estimated 100 million tons of fertilizer on their lawns each year. For every ton manufactured, two tons of carbon dioxide are produced. In addition, the fertilizer that isn’t absorbed by the plants evaporates as nitrous oxide, a greenhouse gas 300 times more potent than carbon dioxide. The rest washes out of the soil and pollutes lakes, streams, and groundwater.

Another interesting fact from the US Fish and Wildlife Service: homeowners use up to 10x more chemicals per acre than farmers.

But, lawns are great to play in.

Yes, yes they are. Turf-grass also makes great pathways. These are both excellent uses and should not be ignored. But we deserve better in our landscapes where it doesn’t make logical sense to grow turf-grass.

5. Meadows are easy to love.

We love our lawns, but apart from the most unapologetic and passionate lawn enthusiasts, I’m convinced many of us could easily fall in love with meadows given the chance to stand in one, or watch one grow. If we do, we’ll see the dried-out look of a late summer lawn replaced by a richly textured, ever-shifting colorscape. And we’ll hear the roar of lawn mowers fall silent so the sound of chirping birds and crickets can rise up and be heard, and we all get to breathe a little easier. (p21)

Meadows offer a unique opportunity to help the planet from our own yards. They support many of the wild things that keep ecosystems healthy and store carbon, too, all without asking for much in return. Grasslands, natural as well as man-made, are also the ideal landscape for our climate-challenged times, thanks to their inherent resilience. If just a fraction of the existing lawns in this country were turned into meadows, the ecological impact, especially on threatened pollinator species, would be immediately significant. (p138)